Research

Overarching goals of our research:

Our long-term research focuses on two major questions, moving from basic biology to potential applications:

• Which parts of the genome control the maintenance, gain, or loss of regenerative ability during vertebrate evolution?

• Is there a shared “genetic toolkit” for limb and fin regeneration that could, in theory, be reactivated in species that no longer regenerate well?

Overall, we believe that studying regeneration through an evolutionary lens — and directly comparing different species — is essential for discovering the molecular and cellular mechanisms that make limb and fin regeneration possible.

Reesearch areas

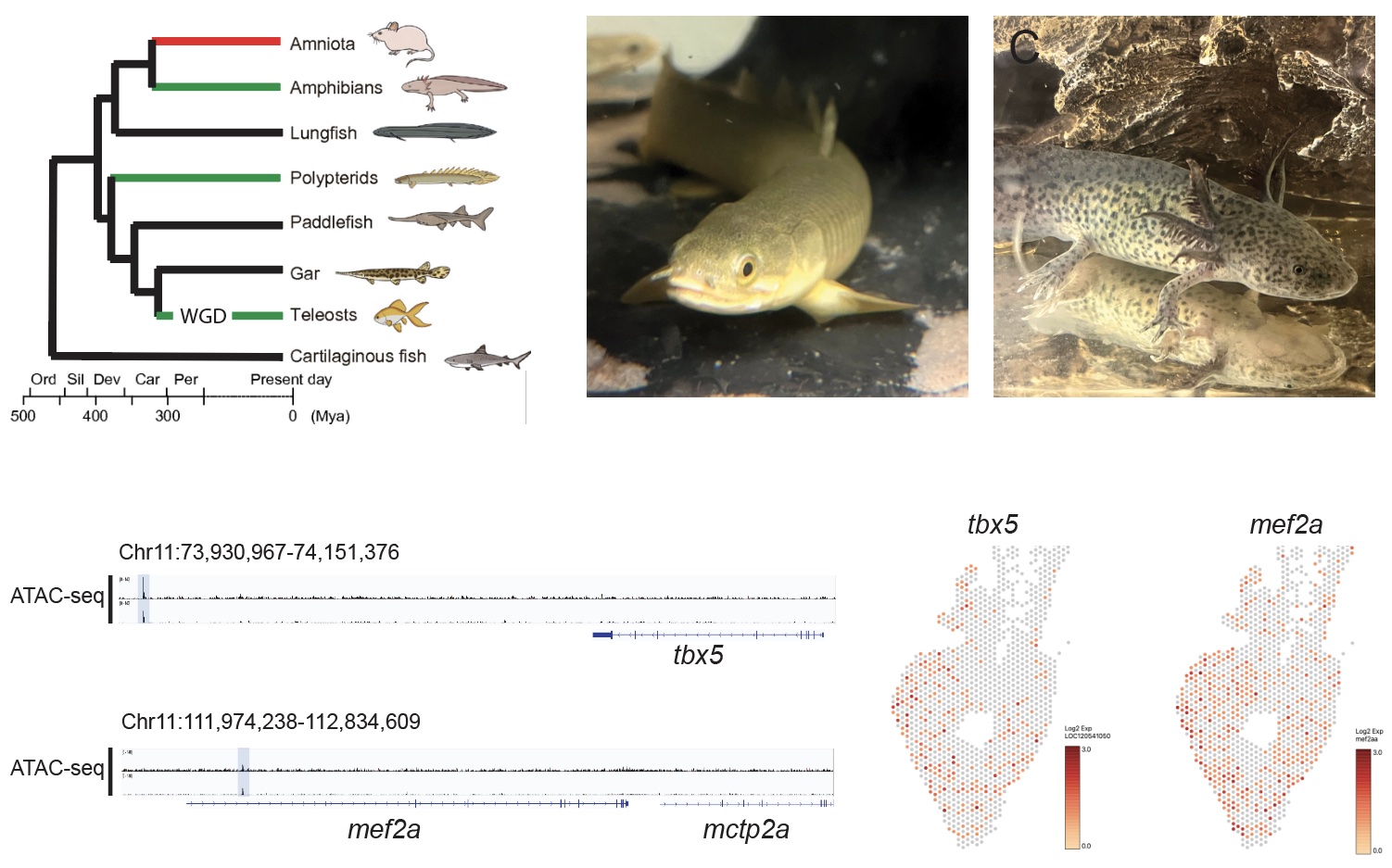

Multiomic analysis of limb and fin regeneration:

The regeneration of limbs and fins involves the recruitment and orchestration of several cell types to rebuild a complex multi-tissue structure. To search for a shared regeneration "toolkit", we investigate the cellular make up and molecular signals that come into action soon after fin/limb loss. What set's our research apart is our comparative approach, taking advantage of the remarkable regenerative abilities of species such as the axolotl, the lungfish, the bichir (Polypterus) and the zebrafish.

Evolution of gene regulatory network of heart regeneration:

Successful heart repair depends on the whether heart muscle cells can multiply in the injured heart. Although this is limited in adult humans, new muscle cells are a major driving force behind heart repair in other animals. Gene-therapy strategies that aim to make heart muscle cells divide again rely on the identification of regeneration-responsive regulatory elements, which act as switches that turn on the right genes and only when the heart is repairing itself. To reach this goal, we are identifying these DNA elements in the axolotl and the bichir—two species that can naturally regenerate their injured hearts.

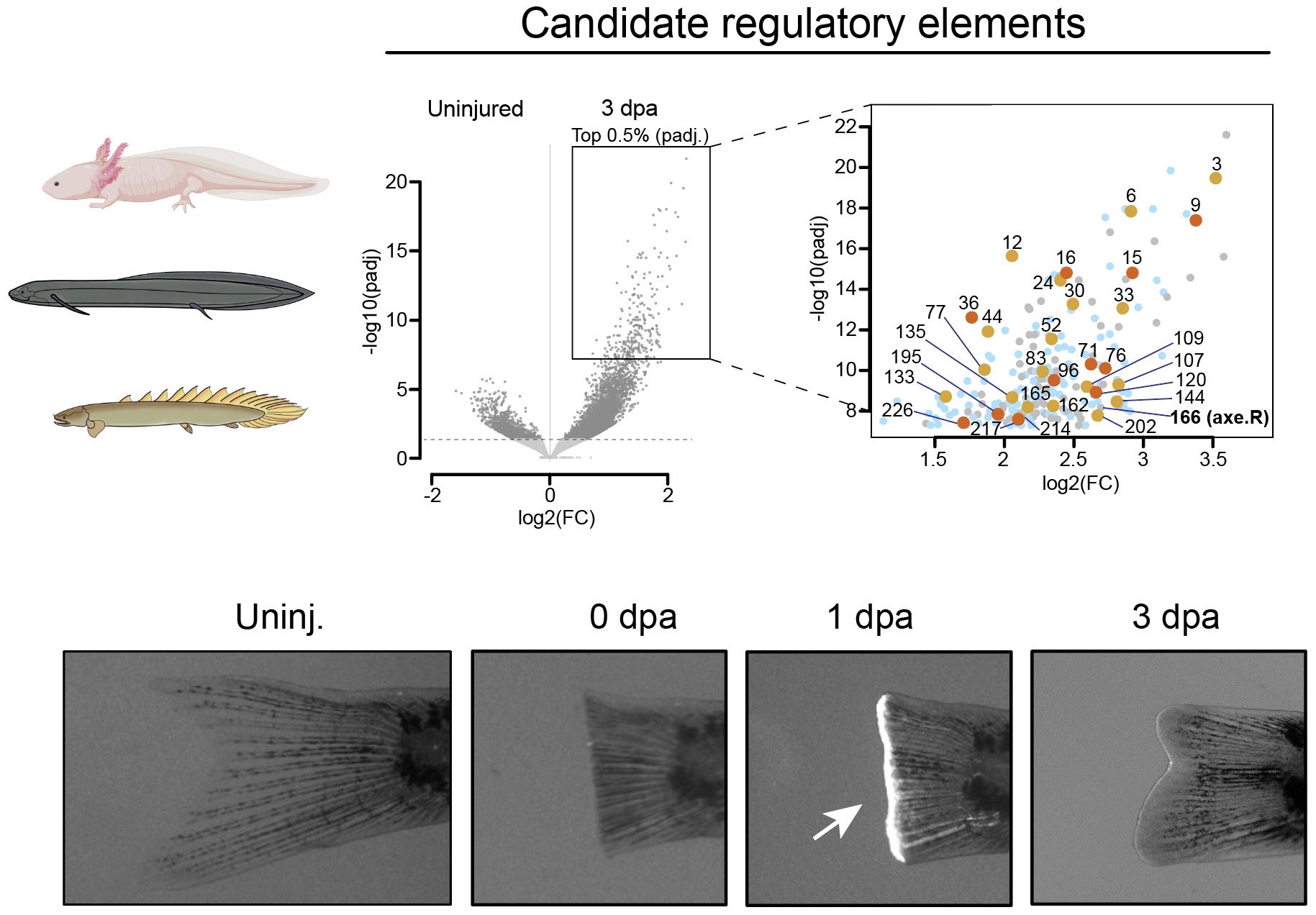

Gene regulatory landscapes of limb and fin regeneration:

In recent years, scientists have discovered sections of DNA—called regulatory elements—that switch on during tissue regeneration in a wide range of animals, from simple worms to many fish species. With new high-quality genomes now available for highly regenerative animals like the axolotl, lungfish, and Polypterus, we can finally test whether some of these DNA switches are shared across evolution and help control limb and fin regrowth. Our work focuses on identifying the conserved parts of this genetic “regeneration program” in vertebrates. By building a large, multi-species dataset of these regeneration-responsive DNA elements, we hope to predict which species are capable of regeneration and gain insight into how regenerative ability has evolved over time.